Ever since Dr. Ian Thompson, Choctaw Archaeologist told me about the endangered river cane I was fascinated to see it. I'm afraid my pictures do not do it justice. The Choctaw and other tribes have numerous uses for it. It used to be in swathes three miles long as far as the eye could see along the water's edge and was called cane breaks. Maybe because it was so dense? We found stands on Jim Stephen's land near Antlers, by the Museum of the Red River, along the Illinois River in Tahlequah, and at the Little River Wildlife Refuge but they were all small stands. I am told it is the only native american bamboo.

Early explorers in the U.S. described vast monotypic stands of Arundinaria called canebrakes that were especially common in river lowlands. These often covered hundreds of thousands of hectares. These have declined significantly due to clearing, farming and fire suppression.[2][3] Prior to the European colonization of the Americas, cane was an extremely important resource for local Native Americans. The plant was used to make everything from houses and weapons to jewelry and medicines. It was used extensively as a fuel, and parts of the plant were eaten. The canebreaks also provided ideal land for crops, habitat for wild game, and year-round forage for livestock. After colonisation, cane lost its importance due to the destruction and decline of canebreaks, forced relocation of indigenous people, and the availability of superior technology from abroad.

Ethnobotanists consider cane to have been extremely important to

Native Americans in what is now the

Southeastern United States before

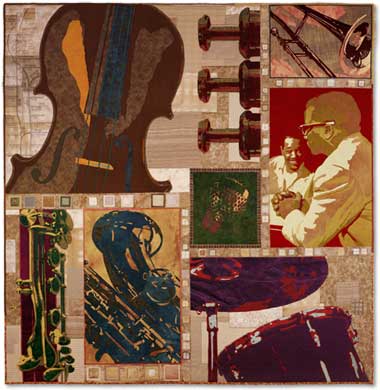

European colonisation. The plant was used to make structures, weapons, fishing equipment, jewelry, baskets, musical instruments, furniture, boats and medicines.

[6] Arundinaria gigantea, or river cane, has historically been used to construct

Native American flutes, particularly among tribes of the

Eastern Woodlands. The

Atakapa,

Muscogee Creek,

Choctaw,

Cherokee, and other Southeastern tribes have traditionally used this material for mat and basket weaving,

[7] and the

Chitimacha and

Eastern Band Cherokee still widely weave with rivercane today.

Food uses include flour, cereal, and even "asparagus" of young shoots; however, caution should be used whenever foraging for cane as, the extremely toxic fungus

Ergot(

Claviceps spp.) has been known to colonize the seeds. Ergot-infected plants will have pink or purplish blotches or growths about the size of a seed or several times larger.

From the site above here is some information about how Contemporary Choctaw use the river cane in their baskets.

Rivercane (commonly spelled both ways, rivercane and river cane) plaited baskets are one of the oldest and best-recognized example of Choctaw traditional craft.

When a basketmaker today searches for, harvests and prepares their river cane, they use the same methods as generations of Choctaw basketweavers did before them. However, most take what they need from modern technology and innovation, but retain the traditions that are important aspects of Choctaw life.

Commercial dyes such as RIT have replaced the natural vegetable dyes of old, allowing a wider range of color choices and as a result, more complexity and interest in the pattern designs. Basketry styles have changed somewhat, too.

New and personal improvements in the weaving design are used to reflect modern-day times. At one time, baskets were made to be used in the field to gather produce and in the home as storage. Modern basket styles often reflect their original functions. Ribbed egg baskets were originally designed to collect fresh eggs safely. Modern laundry baskets are a modified farm basket. And the every popular bushel basket was originally designed to hold fresh produce from the field.

Choctaw basket making begins in the Spring with gathering river cane - a distant relative of Bamboo. This is an arduous task, since river cane grows in damp, swampy areas and is increasingly difficult to find. The taller cane is most prized as less harvesting and preparation is needed by the weaver.

Once the cane is cut, the basketweaver uses a small, sharp knife to slice the thin skin (top) layer into strips. A skilled craftsman can obtain four to six strands from a single piece of cane.

The next step is to dye the cane strands. Originally, basket makers used natural materials such as berries, flowers, roots, or bark to color the cane. When commercial dyes became widely available, they gradually came into use and are used almost exclusively today.

Basket makers create a variety of patterns by weaving together the colored and natural strips of cane. While traditional forms such as the egg basket and traditional patterns like the diamond design are common, many basket makers like to experiment with color, pattern and shape.

Choctaw baskets are prized by collectors, especially the double-wall weave. This technique produces a basket that has two sides, joined by inter-weaving the base and at the rims resulting in a basket that is both exceptionally strong and beautiful.

This basket was done by a Cherokee basketmaker from river cane.

A small stand we found at the Little River Wildlife Refuge near Broken Bow, OK

Historical Uses of River Cane

At one time river cane was an essential resource for the Cherokee and other southeastern tribes. One of the most valued native artifacts is the river cane basket. They occasionally command prices in the thousands. The double weave river cane basket is among the hardest indigenous skills to learn. These baskets are so tightly woven that they were sometimes used to protect tools from rain. Some archaeologists believe that the art of river cane basketry has existed for 6000 years.

The splits were also used to make mats for floors, walls, sleeping and for burials and cremations. They were used to build wattle and daub houses, as well. The river cane “wattles” were woven horizontally among wall posts to form the initial structure. The “daub,” or chinking, consisted of mud and grass pressed into the cane.

Weapons were critical for food and protection in tribal life, and river cane was critical for constructing weapons. The best arrow shafts were made of river cane, because it’s strong and light. Before the bow and arrow, cane was used to make atlatl darts. The atlatl is one of the most primitive projectile weapons, consisting of a spear thrower and a six foot spear, or dart, topped with a heavy stone or bone point. Though other materials such as wood were used, the flex and strength of cane made it perfectly suited for the task. Besides the crossbow, atlatl darts were the only thing that would penetrate plate mail armor. Spanish conquistadors were alarmed to find that their breast plates were useless against them.

The blow gun is another weapon made from river cane. It requires relatively old and thick stalks for its construction. The guns are generally four to eight feet long and ½ to 1 inch thick. Nowadays the nodes of the cane are usually drilled out or burned with steel bits specially made for the purpose, but traditionally they were drilled with a stone bit affixed to a spindle of narrow river cane. Blow guns are very effective for hunting small game such as rabbits and squirrels, and they are still in use today.

Native tribes sometimes caught fish with river cane fish traps and fish spears. The traps were similar to the wire minnow traps we are familiar with. River cane warps and wefts were woven into conically shaped baskets with a small entrance which allowed fish to enter but not escape. The spears were crafted of cane shafts. The ends were either tipped with pronged points or the cane was split to form three or four sharpened spikes. They were usually used to spear fish in shallow water or fish that had been corralled in weirs.

Some tribes even made knives from river cane. The cane was split, shaped and heat treated to make it exceptionally hard. River cane contains silica, the main component in glass, which helped to make the knives effective for shaving. River cane also made good drills for boring holes in rocks. Spindles of wood tipped with river cane bits were spun back and forth by a bow while pressure was applied to the top of the spindle. The cane bits were used with sand to abrade holes. The silica in the cane also contributes to the sanding process, leaving a smooth, clean hole.

Flutes and pipe stems were made from river cane, and river cane flutes are still common today. The holes were traditionally drilled with stone bits.

River cane was also a source of food for indigenous peoples. The tender shoots were gathered and prepared much like bamboo shoots. They were eaten in stews and salads. When river cane flowered, the seeds were collected to be cooked later.

Since prehistoric times river cane has been used for torches. The torches were made by bundling several lengths of cane together, and then beating the ends into feathery tinder so they would catch fire easily. Remnants of burnt river cane torches have been discovered in ancient caves along with char marks, made when the burnt ends were tapped against cave ceilings to knock off the ash.

Restoring Native River Cane

River cane is an easy plant to propagate. It’s usually just a matter of letting it spread. Like other bamboos, it spreads by rhizome, or rootstock, though it’s not invasive like non-native bamboos. The Land Trust for the Little Tennessee (LTLT) is successfully managing a river cane restoration project along the Little Tennessee River near Franklin, NC. They are currently experimenting with different planting techniques to determine what works best. Dennis Desmond, Land Stewardship Coordinator for LTLT, says transplanting cane by digging it in clumps, keeping the entire root ball (as opposed to bare-root) seems to work the best. It should be planted in moist, rich soil. Transplanting usually works best in late winter-early spring.

Planting native river cane at Chattooga River Farm.We have just begun a river cane restoration project on

Chattooga River Farm, the Chattooga Conservancy’s new sustainable agriculture project. Our plan is to eradicate kudzu along a creek and replace it with native cane, which will serve as a stream buffer and eventually as a source of planting stock for other restoration projects and for use in native crafts. The project will take place in several stages with the help of volunteers. Check our website at

www.chattoogafarm.org for updates on our progress.

Please consider starting your own restoration project if you have land suitable for it. You can also help by encouraging the Forest Service to eradicate non-native invasive autumn olives and to let river cane take its place. Send postal mail to:

Robert Jacobs, Regional Forester

USDA Forest Service

Southern Region (R-8)

1720 Peachtree Road NW

Atlanta, GA 30367

Phone: 404-347-4177

This link also talks about projects to restore river cane which is not only endangered but it also threatened by non-native species.

[ Canebrake Restoration ]

Canebrake restoration projects throughout the southeastern U.S. focus on restoring habitat, ecosystem function, and plant materials available for Native American artesians. The restoration of canebrakes enhance habitat for other critically endangered species, including Bachman's warbler. Other parts of the world are using bamboo in restoration of ecosystem function. Canebrakes have several important and unique attributes important for water quality. They are able to increase soil porosity and enhance infiltration of surface water due to the interwoven system of rhizomes and roots and dense culms which disperse and decrease velocity of overland flow uniformly across the ground surface ( 10, 12 ). This combination of attributes demonstrates the vital role this plant community can play reducing sedimentation and non-point source contamination, while the stabilizing of stream and river banks.

Another excellent site for those interested in learning more about Choctaw Basketry....